As promised in my previous post, “A

Tap on the Door of Perception,” this post explores

Eddie Loper Jr’s portrait of me and my portrait of my grandson and his cat. That

said, do you find the title odd?

Since I soon will start teaching a course titled

“Isms Explored” at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute in Wilmington, this

post will illuminate for me and, therefore, for you, how knowing the

characteristics of “isms” and grasping visual ideas recorded in the traditions

of art allow us to evaluate creativity, but in different ways.

Here is Eddie’s portrait of me along with the

photograph that served as his subject. Since he has not yet settled on a title,

I am calling it “Pink Eye,” because that tiny color unit to the right of the

almond shaped “eye” sparks a clue to the painting’s aesthetic meaning.

Fauvism comes to mind, doesn’t it? Every book on “Isms” I read describes the

Fauves (“wild beasts” in French) as a group of painters who applied to their

canvases intensely bright color in rough brushstrokes. Their work tended toward flatness,

non-natural color, and simplification.

Between the years of about 1898 and 1906, Fauvism caused shockwaves, and

Louis Vauxcelles, a critic, gave the movement its name. The independent Salon d’Automne in Paris

presented a selection of works in this style in 1905 (including Henri Matisse,

André Derain, Kees van Dongen, and Maurice de Vlaminck) alongside an Italianate

bust. Vauxcelles proclaimed the

sculpture was like “Donatello parmi les fauves” (a Donatello among wild

beasts).

Here are a few examples of early Fauve work:

Maurice

de Vlaminck, The Bar Counter, 1900, Musee Calvet, Avignon

Matisse,

Woman with a Hat, 1905, San Francisco

Museum of Modern Art

Kees

van Dongen, Woman in a Green Hat, 1905,

Fondation Socindec, Vaduz, Liechtenstein

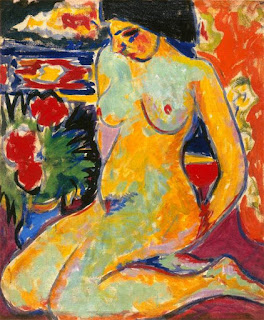

Ernst

Ludwig Kirchner, Nude, c. 1910,

Baltimore Museum of Art

Georges

Rouault, Clown, 1912, MoMA

Eddie’s painting clearly displays Fauvist influence.

If that is all the painting displayed, I would argue

it is merely Fauvism warmed over.

Violette de Mazia coined this phrase by describing a roasted turkey

dinner, one you may have enjoyed during the past holiday season. If you re-heated the leftovers, you would get

“warmed over” turkey. But perhaps, like

me, you made turkey frame soup by first simmering the entire turkey carcass as

well as all the leftover meat and bones in a big pot of water, adding

vegetables, or rice, or noodles along with your own special seasonings. If you did that, you made something new.

Eddie has done that.

We practitioners of the objective method know what

comes next. We examine the painting by

looking for the artist’s use of his plastic means: light, line, color, space,

subject, and tradition. Only then can we

ascertain creativity.

Turning the painting upside down provides the

easiest way to begin because it allows us to focus on what is there: colors on

a flat surface.

Remember I said the pink triangular sliver centered

slightly below the middle of the painting (now to the left) is a clue. Notice how it recedes as the right side of

the “face” and “eye” bulge forward. Notice the teardrop shape of both sections

as the color marks of the lower “face” build a convincing three-dimensional

unit.

The “nose,” looking like a twisted pipe, juts outward to

the right while the color area of upper lip, mouth, and chin puff forward

accentuating the volume that says “face.”

If you follow the pink of the “sclera” (what was the

white of the eye), the rhythmic beat becomes insistent: pink outlines the

“eyes,” the “nose,” and the upper “lip.” A darker line of pink/red moves from

the lower left of the mouth, circles the “pink eye,” culminates at the “hairline,”

then softens to light pink spots in the “hair.”

The “hair” encases the head in a soft, three-dimensional,

pillow-like mound, its color marks lighter than the colors of the “face,”

setting up a dramatic interplay of light/dark motifs.

The warm facial colors contrast with cool upper body

colors, the “turtleneck sweater” another sloping triangular color unit, all of

which contrast with light color washes in the gridded background, gentle echoes

of the foreground unit.

Some of this is borrowed from Soutine, an artist the

“Ism” writers have a tough time placing.

In …isms, Understanding Art,

Stephen Little places him in Modernism, a broad movement encompassing all the

avant-garde isms of the first half of the 20th century. Sam Phillips, in a companion book, places

Soutine in the “School of Paris,” a broad term used to describe the

international community of artists working in the city between the world wars,

and of Soutine, Chagall, and Modigliani, they are, he says, “perhaps the

closest the School of Paris has to defining artworks.”

The following Soutine painting, Self Portrait with Beard, illustrates Eddie’s adaptation of

Soutine’s solid, deep, rich, juicy, and variegated color. In Eddie’s hands,

color is lighter, softer, and drier. According to Dr. Barnes, in work by

Soutine “everywhere there is animation, motion, heightened by variety in the

direction in which the color-strokes run.”

(The Art in Painting, p. 374).

Eddie’s color-strokes, however, run in a more subtle, in and out, back and

forth, motion in deeper space.

1917,

Private Collection

I said I would explore Eddie’s painting and my

painting. However, I am still finishing

my painting, while Eddie has moved on to about 14 other paintings.

Below is my painting “almost” completed. To its

right is the photo I am using as my subject.

Bauman, A Boy and His Cat, 2016?

I do not know where my work fits from the standpoint

of the “isms.” I would place it within

Realism, if such a category existed, but it doesn’t. In some books, the School of London defines

painters who ignored the prevalent trends of Modernism by pursuing figurative

expressionism.

My picture has a strong illustrative aspect with a

decorative appeal because of the vivid, repeating patterns in the “rug” and

“floor.” The colors are vivid, rich, and

bright. The dramatic, tilted perspective

nods toward Cubism because of its shifting viewpoints, but it is Cubism without

the angular shapes or subdued colors.

Upside down, all this is easier to see:

The foreshortening of the body does not look so

distorted right side up. Inverted, the painting looks weird. Now the large head compared to the short arm,

the crinkly outline of the cheek, the knobby knee, the angles of the table, the

patterns on the rug and floor, look bizarre.

Soutine does come to mind again, doesn’t he?

Particularly, this painting:

Soutine,

Woman Asleep over a Book, c. 1937,

Madeleine Castaing, Paris

According to Mme. Castaing, the figure is vertical,

reading with her head leaning back against the arm of a chair or sofa (Soutine, Catalogue Raisonné, p. 760).

If I invert the Soutine, this is how it looks:

To see the visual ideas I adapted from Soutine, I cropped

my picture and placed it next to the inverted Soutine:

In my picture, the color strokes, chiseled, banded, and

pastel-like build a looming “head” that tilts upward and pushes forward in

space.

If you look at the rendering of the “arm” in both

paintings, Soutine’s bulges, a solid, rounded volume like that of a summer

squash, while my “arm,” defined via a series of rectilinear color units,

flattens, a plank-like, hard volume like that of a piece of wood.

Examine my inverted painting again:

Start at the edge of the right side of the face (now

to the left). Look at the ripple. Now

look at the color marks of the red “shirt”; the stripe on the dark blue “shorts”;

the “cat’s tail”; the curl in the “boy’s hair”; the patterns in the “rug”; the

curves of the overlapping “legs.” Look

at the space recession between the figure and the floor and the “cat” and the

table. Look at the contrast of large

curved units like the back of the shirt and the shorts of the “boy” and the large

angular units like the legs and top of the table to the left.

Then look at my painting again, right side up:

The floorboards on top slant right as do the linear

patterns in the rug. The table leg on

the right side of the painting echoes that slant. The top edge of the table,

slanting in the opposite direction, establishes the key spatial drama, setting

figure and cat lower in space, and counterbalancing the “boy’s head,” a large,

brightly colored, solidly ovoid, projecting mass. All of which says “this boy,” “this cat,” on

this “floor,” in this “room.”

Now I need to finish it. You may be wondering how I

know when I am finished. I stop when I can’t find anything that bothers me.

Julian Barnes (no relation to Albert Barnes) writes in his

soon to be released new book Keeping an

Eye Open: Essays on Art, “…in all the arts there are usually two things

going on at the same time: the desire to make it new, and a continuing

conversation with the past. All the

great innovators look to previous innovators, to the ones who gave them

permission to go and do otherwise, and painted homages to predecessors are a

frequent trope.” Julian may not be related to Albert, but

he thinks like him.

If you want to explore more of Edward Loper, Jr.’s work, please

visit his current exhibit Color-Line-Structure

at the Siegel JCC ArtSpace, 101 Garden of Eden Road, Wilmington, DE 19803,

through February 2016. Or you can visit

his website: www.EdwardLoperJr.com.